- The906Report

- Posts

- Would the Copperwood Tailings Basin Endanger Lake Superior? It’s Debatable

Would the Copperwood Tailings Basin Endanger Lake Superior? It’s Debatable

Above-ground storage of mine waste can be disasterous if mismanaged

Mine developer claims risk is low due to elaborate safeguards

Mine opponents argue that significant threats remain

The tailings disposal facility, or “TDF,” would be the single most prominent visual feature at the Copperwood mine. As described in a 2023 feasibility study, the TDF would hold up to 44.6 million tons of mine tailings, the finely ground waste material that remains after ore is crushed and the valuable minerals are extracted in a processing plant.

The mine tailings would be deposited in a 320-acre basin, surrounded on all sides by an embankment, according to the feasibility study. The north face of the embankment would be 151 feet (12-13 stories) tall and would stretch for 1.25 miles east-to-west.

The tailings facility would certainly be visible from the adjacent North Country National Scenic Trail, at least when the trees aren’t fully leafed out, and possibly from other nearby locations.

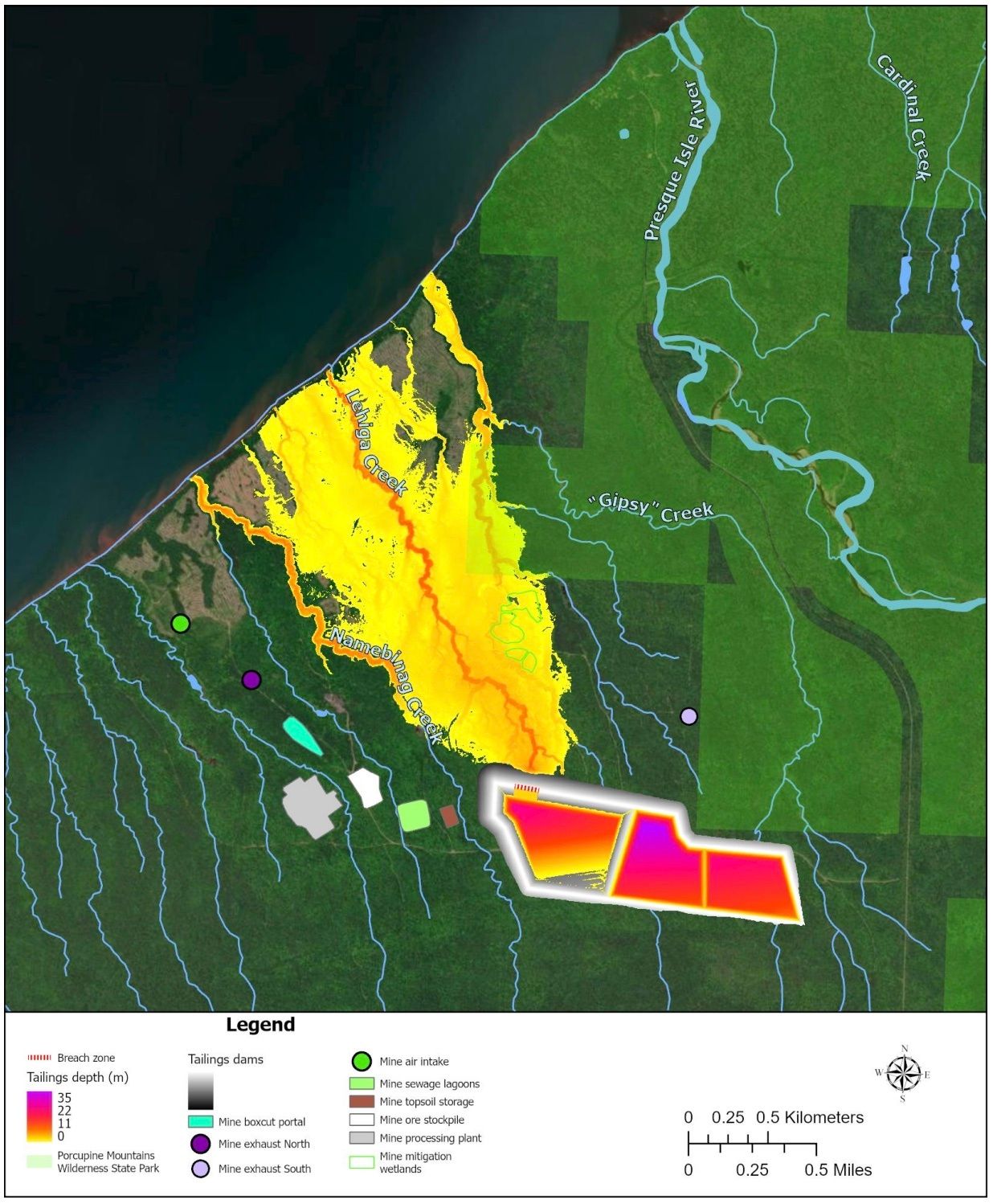

The outline of the Copperwood TDF is visible in this image from Google Maps (overlay added to indicate approximate footprint). The brown scars on three sides of the TDF perimeter are streams that Highland Copper Co., Inc., has rerouted to make way for the future tailings basin.

Tailings disposal facility would be upstream from Lake Superior

Protect the Porkies, a key Copperwood opposition group, states on its website that “for every ton of ore extracted, only 30 pounds would be copper and 1,970 pounds would be waste, containing at least 15 toxins of environmental health concern,” stored directly upstream from Lake Michigan, “the world's largest and cleanest source of surface freshwater.”

The 2023 Copperwood feasibility study acknowledges that mill waste would contain hazardous materials, specifically barium, boron, copper, mercury, selenium, silver, strontium and vanadium. The document describes on-site collection and treatment systems that, according to project owner Highland Copper Co., Inc., would comply with Michigan water quality standards.

Specifically, an impervious clay liner would be installed under the tailings basin, along with an engineered geomembrane liner, according to Highland Copper, to prevent contaminated water from leaking into the environment. Much of this so-called “contact water” would be recycled through the ore processing plant. If it was not reused in the mill, it would be treated prior to discharge into the environment, according to the company.

Protect the Porkies counters that “the mine is guaranteed to pollute,” according to a 2012 study of 14 copper mines then operating in the United States. “At 14 of the 14 mines (100%), pipeline spills or other accidental releases [of toxic materials] occurred,” the study said.

Mine opponents fear consequences of tailings dam collapse

If the Copperwood dam failed catastrophically, “mine waste, up to 14 meters in depth” would surge down watercourses into Lake Superior, according to the Protect the Porkies website, citing a 2024 report from the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLiFWC).

“When the dam breaks, the mine waste will reach Lake Superior in minutes,” warns another opposition group.

Projected flow of mine waste due to a breach of the north dam of the west cell of the proposed Copperwood tailings disposal facility (one of several modeled failure scenarios). Source: Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Unfortunately the GLIFWC dam failure model includes several unrealistic assumptions leading to implausible results that exaggerate the severity of a potential tailings facility failure,” said Copperwood project director Dr. Wynand van Dyk in an email.

“It is widely accepted that the starting point for any breach analysis should be the understanding of credible failure mechanisms of the specific dam,” van Dyk said. Those mechanisms are liquefaction, which occurs when saturated tailings suddenly lose strength and flow like wet sand, undermining the dam structure, and overtopping, which occurs when an extreme rainfall event causes a tailings basin to overflow.

According to van Dyk, neither of those scenarios is likely to occur, due to the design features of the Copperwood project. (More on that later).

Bad things have happened …

Internationally, there have been high-profile tailings dam failures in the past couple of decades.

In 2019, a dam collapse in Brazil killed 270 people and profoundly damaged the environment. This followed a similar incident in 2015. Closer to home, in 2014, the Mount Polley tailings dam collapsed in British Columbia, Canada.

Dramatic video of the incidents (Samarco Fundão Dam; Brumadinho; Mount Polley) was captured and distributed worldwide.

Investigators later determined that design, construction and/or operational defects caused the dam failures to occur (Samarco; Brumadinho; Mount Polley).

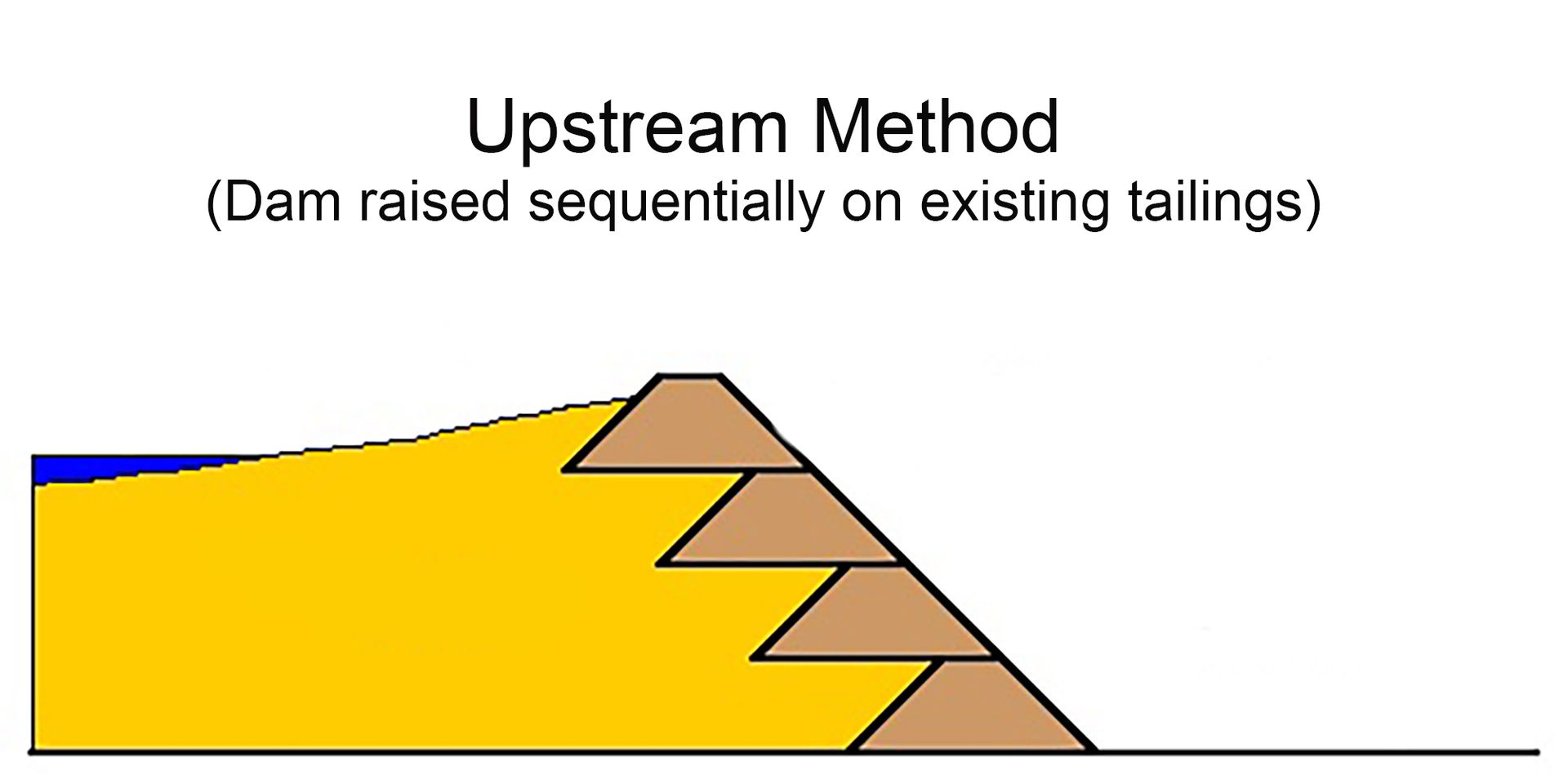

Most existing tailings dams, including the Samarco, Brumadinho and Mount Polley dams, were built with the lower-cost “upstream” method. The dam is raised in stages over time, with each new segment built on top of previously deposited tailings.

Upstream design: new dam segments (brown) are built on potentially unstable tailings (yellow) as the storage basin expands. Source: https://www.wise-uranium.org/mdas.html.

Copperwood dam will be a “single stage” design

“If you go and look at the majority of tailings dam failures, it has always been upstream construction,” said Dr. Wynand van Dyk during an Oct. 24, 2025, site visit for media representatives.

For the Copperwood project, the developer expects to use a different, more reliable method of dam construction, according to van Dyk.

“We've elected to build the entire wall to its final height. So there's no raising. That means, remember, every time you raise something, you create an interface point. You create, in essence, a weak point. If you construct the entire system from the word go, that risk is mitigated,” van Dyk said.

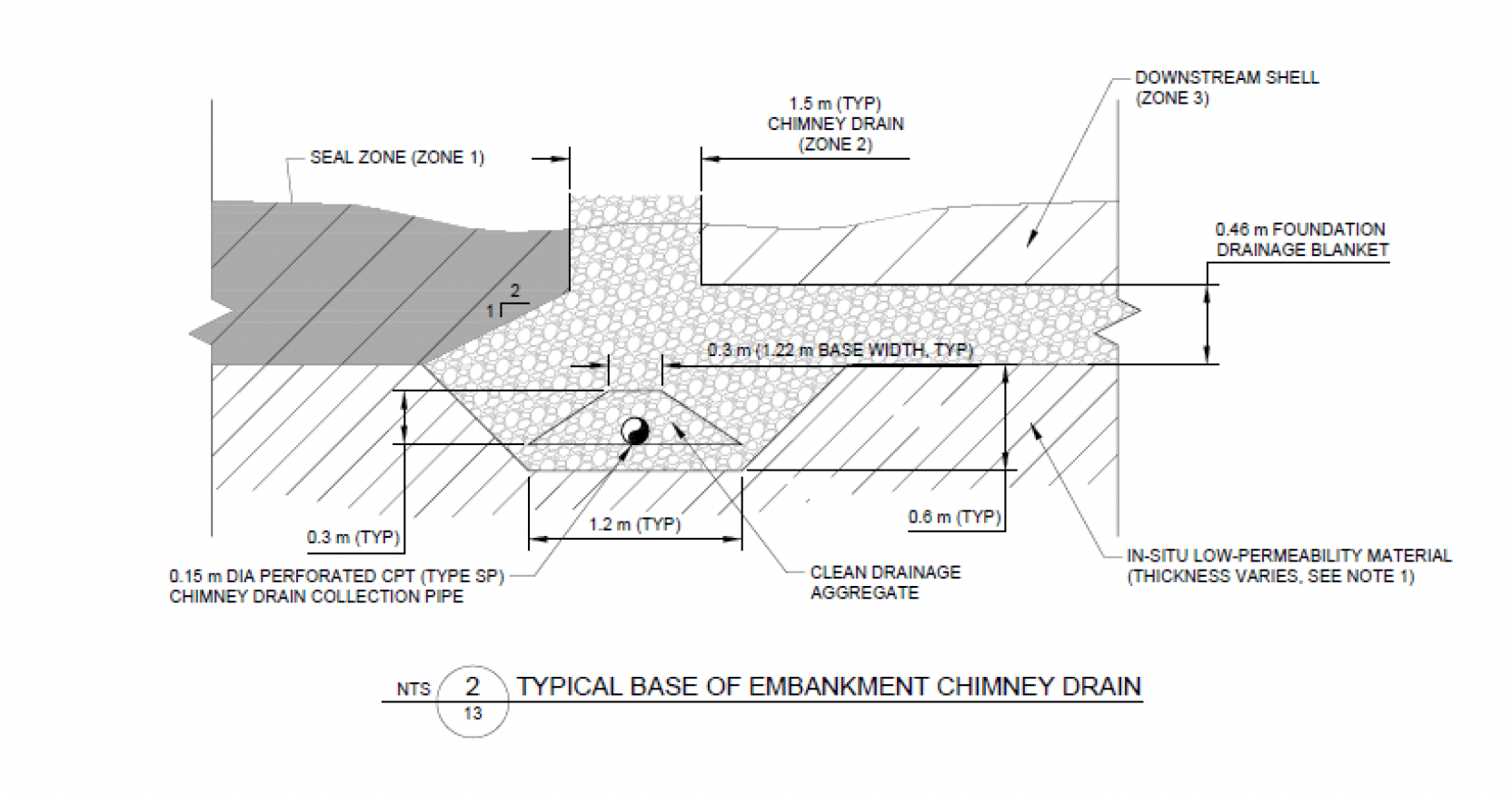

A “chimney” or “curtain” drain down the middle of the Copperwood dam would capture leakage and redirect it before it could potentially weaken the structure, according to Highland’s most recent planning document. Source: Highland Copper, 2023 Feasibility Study Update, Copperwood Project.

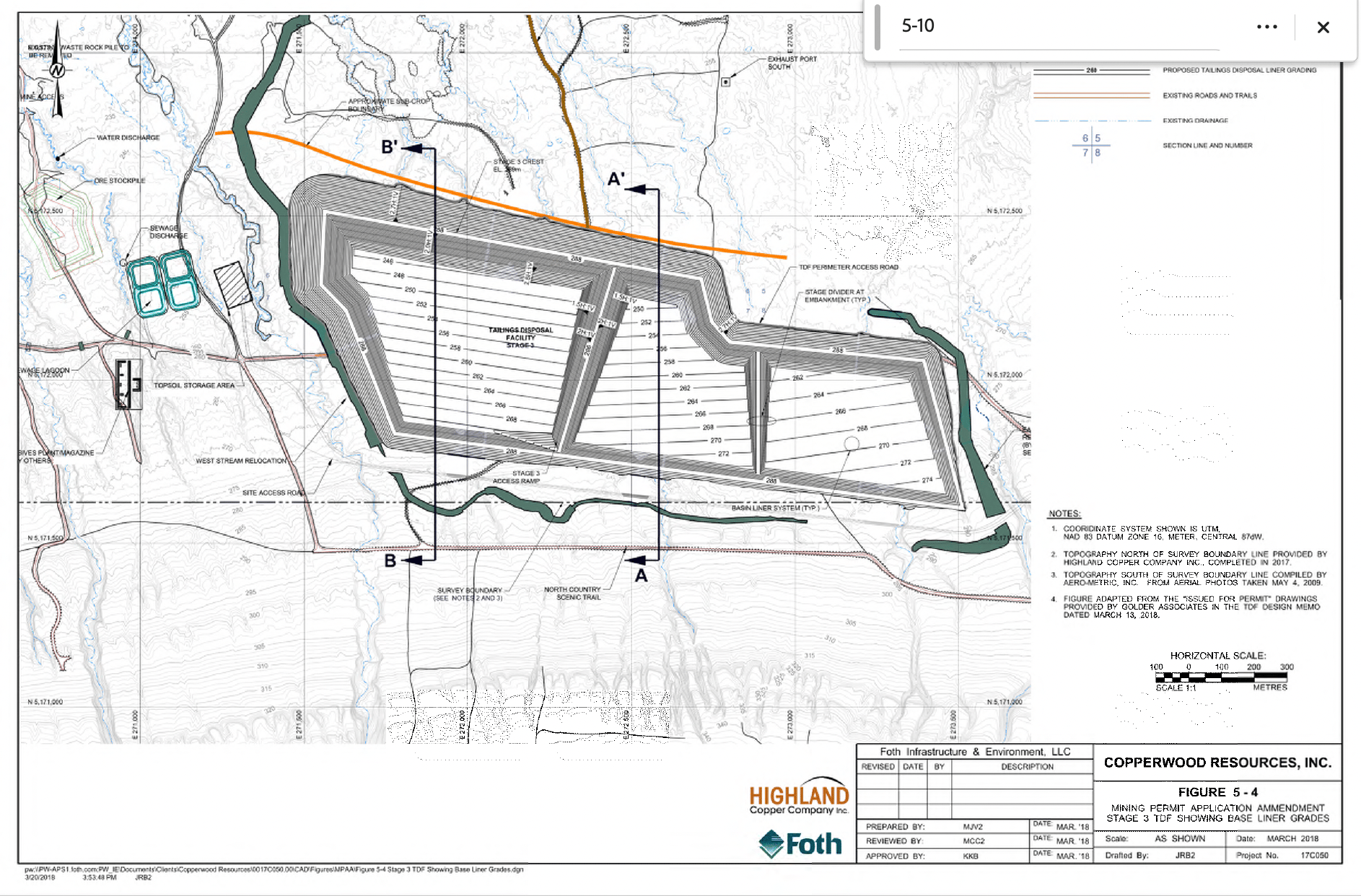

The Copperwood TDF, as proposed, would be constructed in three increments, from east to west, reducing the area of the TDF that is active at any one time.

“These are three independent cells,” van Dyk said during the Oct. 24 media tour of the mine site. “Therefore, should I have a breach, if that happens, you don't have the total volume of the dam that runs out.”

A 2018 regulatory filing shows the three-part construction of the proposed Copperwood tailings disposal facility. Source: Mine Permit Application Amendment, Vol. 1.

Thickened tailings could also reduce the risk of a dam failure, according to van Dyk, although he emphasized that engineers are still working on the final design for the Copperwood project.

It is common practice to pump tailings from a processing mill to a disposal basin as a slurry, with a relatively high water content. At the Copperwood, van Dyk anticipates that the tailings would be dewatered to a mud-like constency.

“If this is just water, you can imagine, should there be a breach, it’s really difficult to stop,” van Dyk said. “If you thicken it up, should there be a breach, it’s thick mud that flows, rather than just liquid. So that's part of the risk mitigation.”

Under this scenario, contact water would not be stored in the tailings basin, van Dyk added. “Not storing water onto a tailings dam is another big risk mitigation,” he said, “so you don't have the risk of overtopping a tailings dam.”

Thickening the tailings also reduces the volume of material that goes into the tailings disposal facility. That change to the original project plan, along with possibly putting some of the tailings back into the underground mine, may allow Highland to reduce the footprint of the tailings basin in the final design significantly, according to an October, 2025, corporate news release.

Exploratory studies show the Copperwood dam is on solid ground, company says

The Copperwood site has a very low earthquake risk, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Exploratory drill holes show that the tailings dam would rest on glacial till (a mixture of clay, silt, sand, gravel, cobbles, and boulders) and bedrock “suitable to serve as a foundation,” van Dyk said. No mining would occur beneath the dam.

“Given that the glacial till is a suitable foundation and that no other dynamic forces can act on the structure, the risk of dynamic liquefaction [due to stress] is minimized,” van Dyk said.

Climate change is dam-safety wildcard

Protect the Porkies questions whether the Copperwood dam could resist increasingly severe, climate-driven rainfall events.

“Since the mine is projected to run only 10.7 years, the company has designed all infrastructure — including the waste dam — to anticipate 1-in-100 year storm events,” Protect the Porkies says on its website, “despite the fact that there have been two 1-in-1000 year storm events in the immediate area in just the last decade. Clearly, ‘thousand-year storms’ need to be renamed, and assuming that another will not happen during the mine life is the definition of a gamble, in unprecedented proximity to Lake Superior.”

A 2016 flash flood in far western Gogebic County caused widespread road washouts and stranded residents. Photo: Gogebic County Road Commission.

“The two 1-in-1000 year events referred to by Protect the Porkies were the July 11, 2016, event in the Western UP and the June 17, 2018 event in Houghton County (also known as the ‘Father’s Day Flood’),” Copperwood project director Dr. Wynand van Dyk said in an email. “The 2016 event recorded 6 to 10 inches of rain over a 6 hour timespan, whereas the 2018 event recorded about 7 inches of overnight rain.”

With a design freeboard of 4.6 feet between the tailings and the top of the dam, “the Copperwood tailings disposal facility could comfortably absorb both these events even if they occurred back-to-back,” van Dyk said.

The greatest recorded 24-hour rainfall in Michigan was about 13 inches in 2019, and the Copperwood dam “will be able to comfortably pass this state record,” van Dyk added.

Mine opponents question adequacy of state dam safety program

The Copperwood tailings dam is subject to permitting under Part 315, Dam Safety Regulations, of the Michigan Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act. The law requires that a large, high-hazard-potential dam must be able to resist “the half-probable maximum flood” (the largest flood that may reasonably occur). The absolute minimum, for a low-hazard-potential dam, is “the 100-year flood, or the flood of record, whichever is greater.”

The Copperwood dam will exceed the state-mandated safety standards, van Dyk said during the Oct. 24 media site visit, and would factor-in climate change. However, he couldn’t provide specifics at the time.

The Michigan dam safety law requires high-hazard-potential dams to be inspected every three years by a licensed professional engineer – either a consultant or a staff member from the Michigan Dept. of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE). Consultant reports must be reviewed by EGLE staff for accuracy and completeness.

However, the Protect the Porkies coalition asserts that “Michigan's dam safety program is not prepared” to oversee the Copperwood project.“ A report from the Association of State Dam Safety Officials states that Michigan's Dam Safety Program is ‘extremely understaffed to perform the mission of dam safety as required by rules, legislation, and best practice,’” the group’s website says.

According to state regulators, the dam safety program has increased staff from two positions to eight full-time specialists overseeing about 1,000 state-regulated dams. This after two dams failed spectacularly in downstate Midland and Gladwin counties.

“Thanks but no thanks” — Protect the Porkies

Mine opponents and Highland Copper Co., Inc., were given the opportunity to review this report prior to publication. In response to a request for comment, Tom Grotewohl of Protect the Porkies provided the following statement:

Although the downstream TDF design is more reliable than upstream, there are nonetheless instances of rupture, which is why such extreme proximity to Lake Superior — the largest and cleanest source of surface freshwater on the continent — should not be considered.

With or without a rupture, there are numerous other ways that mines contaminate the water and environment, and the Upper Peninsula is still struggling to remedy the fallout from past mining endeavors.

Finally, Protect the Porkies recommends that everyone take a look at the Upper Peninsula from Google satellite. The waste piles of the Tilden / Empire Mines in Marquette County, and of the White Pine Mine in Ontonagon County, constitute massive, permanent scars on the landscape. The White Pine facility alone could contain twenty-four Pyramids of Giza. These are among the largest man-made constructions on planet Earth, and their locations must be carefully weighed.

Copperwood's tailings basin would remain as a monument of waste, perpetually visible from the Lake of the Clouds Overlook, the North Country Trail, and Copper Peak, requiring permanent maintenance.

And what are we getting in exchange for so much waste? Boom-and-bust jobs, copper shipped out of country, and a Canadian company enriched.

Thanks but no thanks.

“We demand the company take every precaution” — Citizens for a Safe and Clean Lake Superior

Statement from Jane Fitzen, Director of CSCLS:

As advocates for clean water, we demand the company take every precaution to prevent a release of toxic mine waste into Lake Superior and her tributaries. We are encouraged by the company's new plan to store some tailings underground, lowering the threat of tailings failure, and continuous engineering of the tailings dam to be more secure.

However, regardless of the engineering and design that has gone into the design so far, it's important to remember that this is a massive, permanent, open-air tailings holding tank we're talking about. It has already caused the permanent destruction of 60 acres of wetlands and many streams, the homes to countless wildlife and tributaries of Lake Superior. As an open-air tank, there is significant potential for birds to land and get stuck in the tailings slurry.

We must consider the many types of impacts a tailings dam of this size inflicts on its surrounding natural communities. At the end of the day, this is still a toxic waste dam, taller than the Statue of Liberty, that would remain on the shore of Lake Superior for every future generation; much longer than any mining company or governmental regulator would exist to monitor it.

Final part of a three-part series. Read the previous reports at The906Report archive page.

All statements attributed to the websites of Protect the Porkies and Citizens for a Safe and Clean Lake Superior were correct as of Dec. 12, 2025. Changes may have occurred since that date.